Patriotism

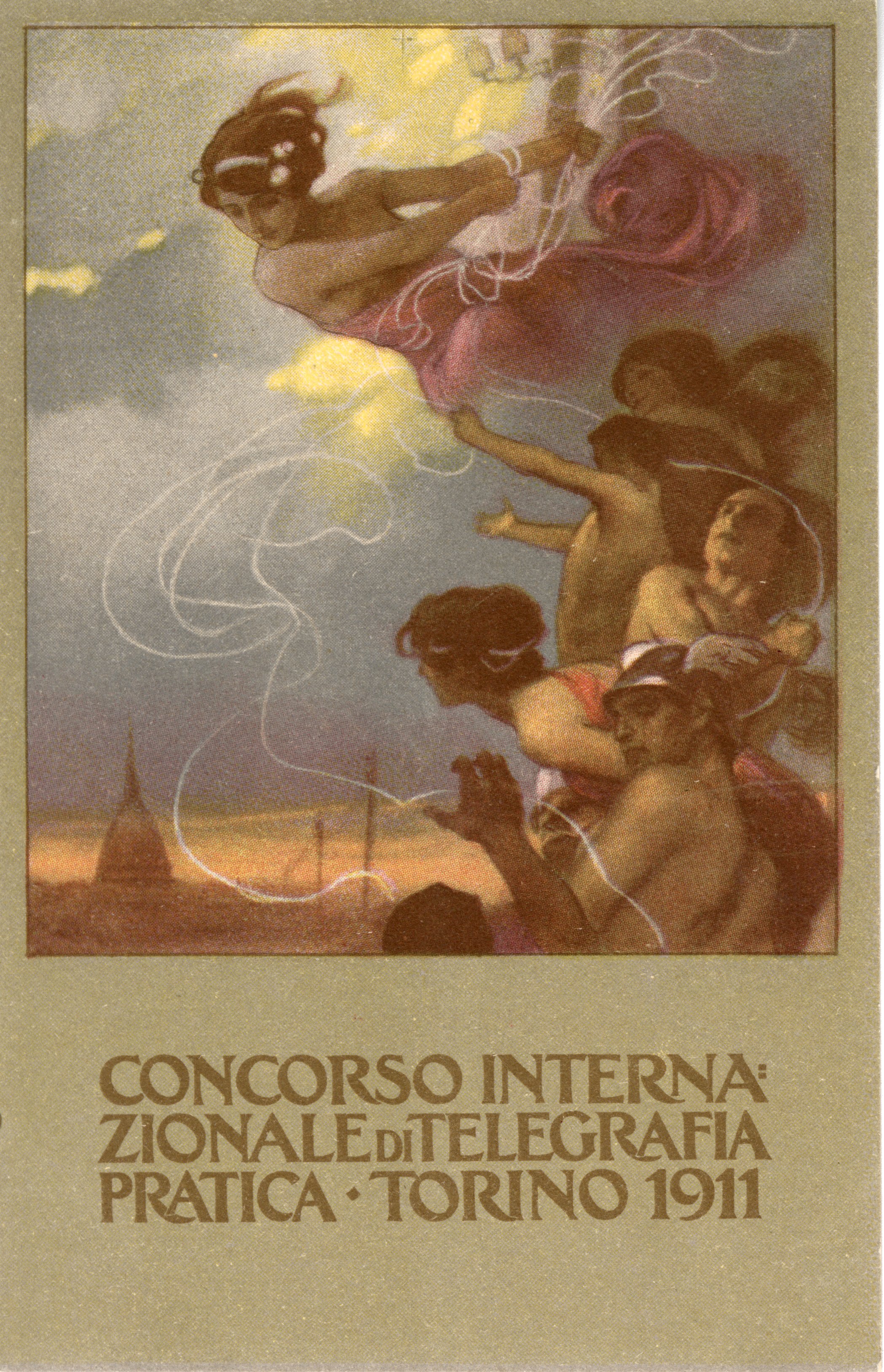

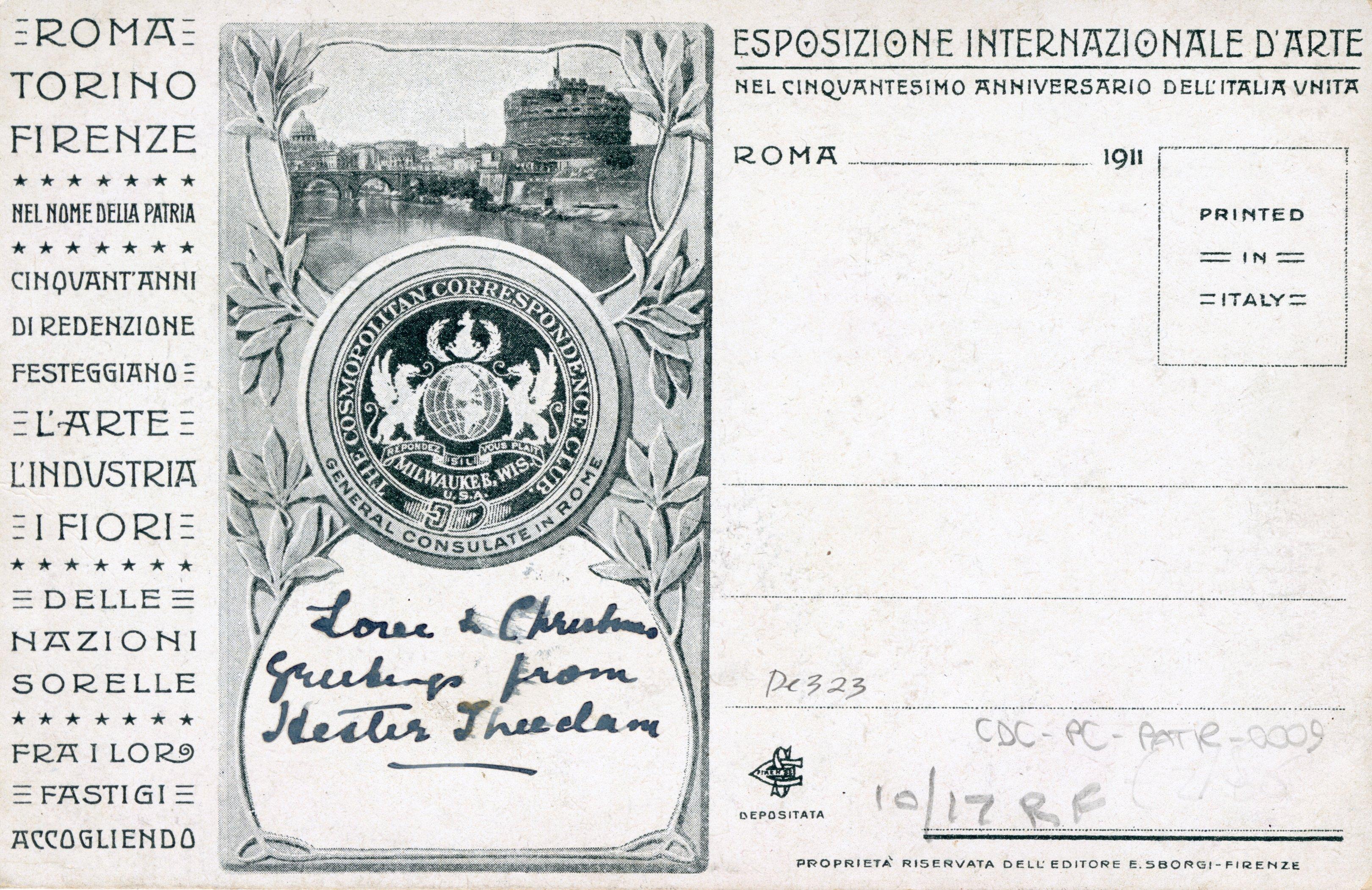

Since the fabled Crystal Palace exposition in London’s Hyde Park in 1851, World’s Fairs constituted ordered display cases of goods as well as ideas. Like the merchandise exhibited for the public’s desiring eyes, these ideas were arranged and packaged for quick assimilation and eager consumption. If the Expositions’ cornucopia of commodities stunned the fairgoer with a sense of abundance, extravagance, and novelty, the power of the World’s Fairs’ ideas derived from the fact that they were both few and redundant.

From one Fair to the next, recurring notions displayed themselves in novel garb: They were notions about national identity and exotic otherness, imperial competition and civilization’s advance, social stability and capitalist growth, and technological progress and bourgeois affluence. Kaleidoscopic in their arrangement of elements, World's Fairs exploited recurring ordering and characterization principles that hierarchically ranked and objectified societies, confirmed the preeminence of host nations and, as a whole, asserted the supremacy of western civilization.

On the all-inclusive stage of universal expositions, differing ideologies, multiple messages, and contrasting representational codes nonchalantly coexisted: Nationalism married cosmopolitanism, the gospel of world peace included statements of martial might and colonial aggression, the display of regional and ethnic particularities cohabited with globalizing drives, and intimations of realistic accuracy flaunted spectacular artifices. Janus-like, the World’s Fairs’ founding ideas were thus both normative and integrative, heralding the future while remaining tradition-bound — they were parochial as well as universal, unifying yet Manichean. This ideological omnivorousness made World’s Fairs formidable consensus-creating machines, operating on efficient technologies of social stabilization and cultural homogenization.

Related Secondary Sources

Related Archival Material